King Bhumibol (Rama IX) is the longest serving head of state in the world, having come to the throne some six decades ago. Over the years his stature has steadily grown, as has his influence, and today his standing amongst the people of Thailand far exceeds any of its political leaders. King Bhumibol’s achievement reflects his personal qualities as well as the country’s need for a symbol of unity. Even in the 21st century, although Thailand is in some respects a reasonably successful development, its problems – political, social and economic – remain considerable and the King’s steady and undeniably wise hand at the helm has been a vital factor in keeping the peace and allowing a good deal of progress to be made. Recently the King has intervened in the mounting crisis surrounding current premier Thaksin Shinawatra. Thaksin is a figure typical of Thai politics. The richest man in the country, at least until he gave his businesses over to family and friends, he entered politics in 1994 and allegedly used his position to ensure his financial interests were safe during the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997. Thaksin survived several scandals and eventually rose to become PM in 2001, running on anti-corruption ticket. Big business and politics are pretty much the same thing in Thailand and, predictably enough, Thaksin’s dual role has led him into a series of actions that many feel represent a huge conflict of interest, the culmination coming with the scandal that broke out on Monday January 23rd, 2006, just three days after the new ‘Thai Telecommunication Act’ was passed. The premier’s family sold all its shares in Shin Corporation, a leading communication company, to Temasek Holdings with tax liability exemption. The Shinawatra and Damapong (the family of Thaksin’s wife) made a fortune, in the region of 73 billion baht (aprox US$1.8 billion) from the buyout. The loophole they used was that the new regulations stipulate that individuals (as opposed to corporations) who sell shares on the stock exchange pay no capital gains tax. So, although it may be by the letter of the law, it is not in the spirit of clean politics and a massive outcry ensued. Not only is the extraordinary profit outrageous the Shin Corporation, which is the dominant player in Thailand’s information technology sector, is now in the hands of the Singaporean government.  King Bhumibol has made his displeasure over the affair known whilst popular protests have grown, culminating with a mass rally in the capital, Bangkok, on February 4. Thaksin’s response came in his weekly radio address: “A majority of the people want me to continue working. Only the king can ask me to resign. If he whispered to me, ‘Thaksin you can quit now,’ I would prostrate myself at his feet and step down immediately, I will not surrender otherwise.” It showed his guile as the King would not wish to intervene crudely and, despite his flaws, Thaksin is a complex figure not without his merits. Although he comes from the ruling class of powerful business families, until 2004 Thaksin seemed to be an effective leader and the country’s still fragile democracy seemed in reasonably good hands. If he has proven to be self-interested that is nothing new. It is also noteworthy that his government has taken some measures that the King would not disapprove of, such as giving cheap loans to farmers and subsidizing health care. Some even credit Thaksin with pulling the country out of the post-1997 economic slump. Presiding over the nation’s best interests, King Bhumibol often appears enigmatic and even hesitant but his stature is undeniable. Undoubtedly, six decades on the throne have taught him a great deal, not least to be patient during a crisis. Whilst that can at times seem like impotence, the royal presence is a constant one exerting a gravitational pull on all sections of the nation. The King’s constancy is the unifying point for the nation, his philosophy a combination of progressive politics and Buddhism that can be traced back to his formative years as a young man growing up in Europe. King Bhumibol was born in 1927, the second son of Prince Mahidol and his commoner wife, Sanguan Talpat. Both his parents were western-orientated and fervently hoped that Thailand would change from a traditional, and in some respects still feudal, society, and follow the European example of popular democracy. Mahidol had little desire to become king but was made heir apparent following King Vajiravudh’s death in 1925, and would have eventually come to the throne if he had not met a premature death in 1929. His passing left Sanguan with their three children to raise: daughter Galyani, Nan (later King Ananda) and Lek (later King Bhumibol). Sanguan was a remarkable woman of considerable intellect and a voracious appetite for knowledge. She had the foresight to keep the family out of Thailand during the 1930s when the country fell under the rule of the military and a quasi-fascist leadership hostile to the monarchy. In exile in Switzerland, Nan was nominally king and did return fleetingly to the country before the outbreak of WWII. Wisely Sanguan took the family back to Europe whilst Thailand entered the war allied to Japan. Inevitably Japan’s defeat led to political changes. The right-wing militarist Pibul Songkhram fell from favour and the left-wing Pridi Phanomyong stepped in, favouring the return of the monarchy as a support to his government. So King Ananda assumed the throne. The young monarch was just twenty years old and inspired by idealistic thoughts of presiding over an era of reconstruction and democracy. However, Ananda’s life was cut tragically short on June 9, 1946. The definitive version of his death has yet to be given. The official verdict is still suicide but it is suggested by King Bhumibol’s biographer, William Stevenson, that the notorious Japanese war criminal Tsuji Masanobu, in league with Pibul Songkhram, was the culprit. For young Lek it was a great tragedy. His relationship with his brother had been a very close one. Worse still, suspicion fell on Lek and his mother and it was rumoured that Lek had killed his brother to get to the throne. They could not defend themselves against the rumours for fear of sending the country into political turmoil. It was, however, an unlikely scenario unsupported by the known facts and of what we know about Lek as a person. He had not wanted the throne and was hoping to be able to return to his life in Switzerland. Furthermore, politics was not his passion. He loved the arts, in particular music, and found the feudal ceremony and mores of the royal court oppressive in the extreme. In fact of the three returnees (Galyani had married and stayed behind in Europe), King Ananda had been the keenest. His mother had had her doubts about the timing for the monarchy’s return and for the family’s safety. For his part, Lek was not expecting to come to the throne and had expected to play a secondary role to his brother. King Bhumibol, therefore, came to the throne of Thailand unwillingly, in the worst possible circumstances. After his accession he would soon leave again and the country would fall back under the sway of Pibul Songkhram by 1948.

King Bhumibol has made his displeasure over the affair known whilst popular protests have grown, culminating with a mass rally in the capital, Bangkok, on February 4. Thaksin’s response came in his weekly radio address: “A majority of the people want me to continue working. Only the king can ask me to resign. If he whispered to me, ‘Thaksin you can quit now,’ I would prostrate myself at his feet and step down immediately, I will not surrender otherwise.” It showed his guile as the King would not wish to intervene crudely and, despite his flaws, Thaksin is a complex figure not without his merits. Although he comes from the ruling class of powerful business families, until 2004 Thaksin seemed to be an effective leader and the country’s still fragile democracy seemed in reasonably good hands. If he has proven to be self-interested that is nothing new. It is also noteworthy that his government has taken some measures that the King would not disapprove of, such as giving cheap loans to farmers and subsidizing health care. Some even credit Thaksin with pulling the country out of the post-1997 economic slump. Presiding over the nation’s best interests, King Bhumibol often appears enigmatic and even hesitant but his stature is undeniable. Undoubtedly, six decades on the throne have taught him a great deal, not least to be patient during a crisis. Whilst that can at times seem like impotence, the royal presence is a constant one exerting a gravitational pull on all sections of the nation. The King’s constancy is the unifying point for the nation, his philosophy a combination of progressive politics and Buddhism that can be traced back to his formative years as a young man growing up in Europe. King Bhumibol was born in 1927, the second son of Prince Mahidol and his commoner wife, Sanguan Talpat. Both his parents were western-orientated and fervently hoped that Thailand would change from a traditional, and in some respects still feudal, society, and follow the European example of popular democracy. Mahidol had little desire to become king but was made heir apparent following King Vajiravudh’s death in 1925, and would have eventually come to the throne if he had not met a premature death in 1929. His passing left Sanguan with their three children to raise: daughter Galyani, Nan (later King Ananda) and Lek (later King Bhumibol). Sanguan was a remarkable woman of considerable intellect and a voracious appetite for knowledge. She had the foresight to keep the family out of Thailand during the 1930s when the country fell under the rule of the military and a quasi-fascist leadership hostile to the monarchy. In exile in Switzerland, Nan was nominally king and did return fleetingly to the country before the outbreak of WWII. Wisely Sanguan took the family back to Europe whilst Thailand entered the war allied to Japan. Inevitably Japan’s defeat led to political changes. The right-wing militarist Pibul Songkhram fell from favour and the left-wing Pridi Phanomyong stepped in, favouring the return of the monarchy as a support to his government. So King Ananda assumed the throne. The young monarch was just twenty years old and inspired by idealistic thoughts of presiding over an era of reconstruction and democracy. However, Ananda’s life was cut tragically short on June 9, 1946. The definitive version of his death has yet to be given. The official verdict is still suicide but it is suggested by King Bhumibol’s biographer, William Stevenson, that the notorious Japanese war criminal Tsuji Masanobu, in league with Pibul Songkhram, was the culprit. For young Lek it was a great tragedy. His relationship with his brother had been a very close one. Worse still, suspicion fell on Lek and his mother and it was rumoured that Lek had killed his brother to get to the throne. They could not defend themselves against the rumours for fear of sending the country into political turmoil. It was, however, an unlikely scenario unsupported by the known facts and of what we know about Lek as a person. He had not wanted the throne and was hoping to be able to return to his life in Switzerland. Furthermore, politics was not his passion. He loved the arts, in particular music, and found the feudal ceremony and mores of the royal court oppressive in the extreme. In fact of the three returnees (Galyani had married and stayed behind in Europe), King Ananda had been the keenest. His mother had had her doubts about the timing for the monarchy’s return and for the family’s safety. For his part, Lek was not expecting to come to the throne and had expected to play a secondary role to his brother. King Bhumibol, therefore, came to the throne of Thailand unwillingly, in the worst possible circumstances. After his accession he would soon leave again and the country would fall back under the sway of Pibul Songkhram by 1948.  The coup d’etat had been successful. Oddly enough it meant that the country reverted back to the political scene of the late 1930s with Pibul Songkhram in charge and the King’s uncle, Prince Rangsit, acting as regent. Yet the military strongman was no longer strong enough to have Rangsit imprisoned as he had done before the outbreak of WWII and, dependent on how the political situation developed, King Bhumibol could be expected to return sometime in the reasonably near future. For Lek it was a relief. Apart from the family’s safety being at risk, returning to Europe meant he could get back to a normal life. However, he changed the focus of his studies from literature – he had already gained the baccalauréat de lettres (high-school diploma with major in French literature, Latin, and Greek) at the École Nouvelle de la Suisse romande, in Chailly-sur-Lausanne – to Law and Political Science, feeling this would give him a better grounding now that he was king. It also gave Lek the chance to marry and start a family. Whilst he was nearing the end of his studies in Switzerland, he visited Paris frequently. It was there that he met a distant cousin , Mom Rajawongse Sirikit Kitiyakara, daughter of the Thai ambassador to France and, thereafter, he regularly visited the amabssador’s family home. Whilst the relationship was developing Lek was seriously injured in a car accident. He lost an eye and needed to be hospitalized in Lausanne. Mom Rajawongse Sirikit (later known as Queen Sirikit) was a regular visitor and also met Sanguan, who suggested she continue her studies in Lausanne. She agreed and Lek chose Riante Rive, a boarding school in Lausanne for her. Their engagement came in Lausanne on July 19, 1949 and they were married the following year, on April 28, 1950. The couple went onto have four children: Princess Ubol Ratana, born on April 5, 1951; HRH Crown Prince Maha Vajiralongkorn, born July 28, 1952; HRH Crown Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn, born April 2, 1955 and HRH Princess Chulabhorn Walailak, born July 4, 1957. Lek’s coronation came a month after his marriage. It was an impressive event and gave him an indication of the latent influence the monarchy potentially had. News of the return of the king spread rapidly and, as he disembarked on Bangkok’s riverway, hundreds of thousands of cheering people greeted him. There were in fact two coronations – thee Spritiual Coronation of the late King Ananda (giving the deceased a fitting burial has great importance in Buddhism) and the new King’s. Both ceremonies were held within twelve days with a splendour that recalled the glories of the monarchical past. That the people still had a genuine veneration for the monarch Lek saw the evening after Nan’s cremation. Hundreds of thousands stayed with the late King’s ashes and Lek joined the crown anonymously. Dressed casually he was just another young Thai. The King had returned but it was a circumspect return reminsescent of King Ananda’s brief 1938 visit. With Marshall Pibul still in control of the country and the US prepared to support virtually any polity so long as it was not communist, Thailand was hostile territory politically, and to the people the King was more like a figure from a fairytale than a living, breathing monarch. Marshal Pibul’s jealousy had nonetheless been enrage and he was busy staging political provocations with the aim of having the King sign a new constitution that would, supposedly, restore Thai democracy, whilst in reality positioning himself for absolute power. Lek was better prepared for him now. He would later recall : “Political science textbooks in Lausanne were no use to me. I got more out of reading ‘Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Musashi’s Japanese ‘Book of Five Rings’ and Machiavelli’s ‘The Prince’. They were masters in the art of winning battles without waging open war.” So well did the King mask his true feelings his enemies were constantly surprised when he acted. The King’s return sparked an intricate game of political powerplays. Rather than appear in kingly regalia, Lek had stepped ashore in Bangkok wearing an ordinary suit so that the people would see the monarch was just like them. A deft populist touch to unbalance the politicians who saw him as little more than a spoilt brat who needed to be put in his place. Pibul’s game was to entrap the King in the capital and keep the countryfolk out with a military cordon whilst he was ‘convinced’ to sign the constitution. Instead Lek asked to see the great Buddhist temples and began an impromptu tour of the country; his instincts told him to show himself to the people. Politically it was also a tense time, with rumours of 200,000 Chinese troops preparing to invade Indochina. Thailand’s assigned role as a US ally in the cold war was as the South-East Asian nation that must, whatever the costs, not be allowed to fall to communism.

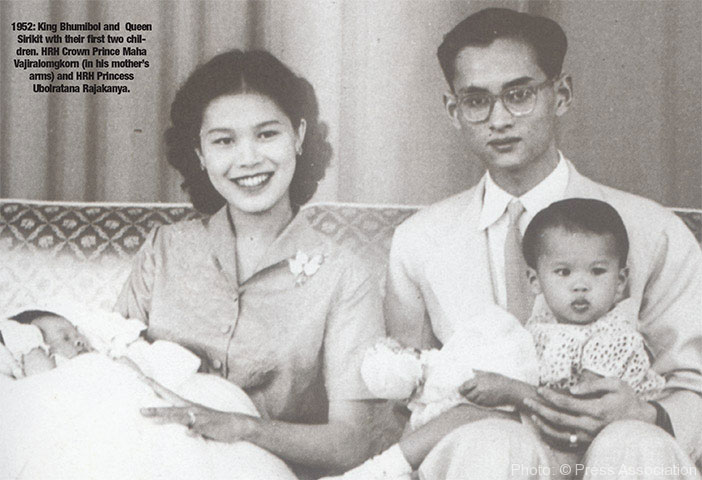

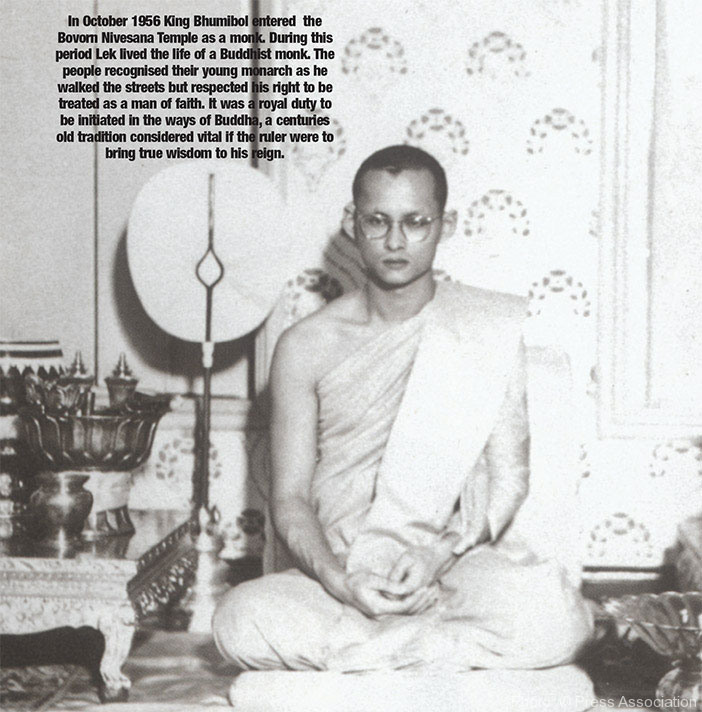

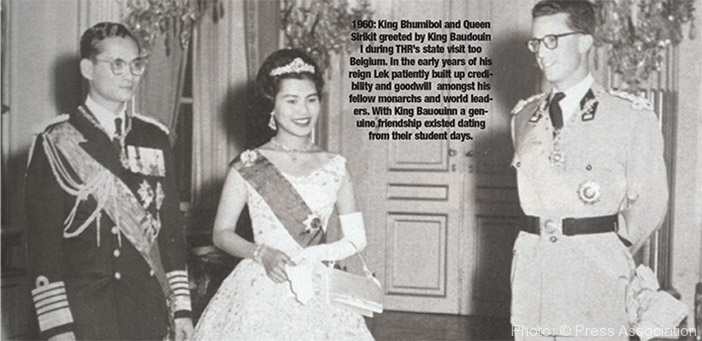

The coup d’etat had been successful. Oddly enough it meant that the country reverted back to the political scene of the late 1930s with Pibul Songkhram in charge and the King’s uncle, Prince Rangsit, acting as regent. Yet the military strongman was no longer strong enough to have Rangsit imprisoned as he had done before the outbreak of WWII and, dependent on how the political situation developed, King Bhumibol could be expected to return sometime in the reasonably near future. For Lek it was a relief. Apart from the family’s safety being at risk, returning to Europe meant he could get back to a normal life. However, he changed the focus of his studies from literature – he had already gained the baccalauréat de lettres (high-school diploma with major in French literature, Latin, and Greek) at the École Nouvelle de la Suisse romande, in Chailly-sur-Lausanne – to Law and Political Science, feeling this would give him a better grounding now that he was king. It also gave Lek the chance to marry and start a family. Whilst he was nearing the end of his studies in Switzerland, he visited Paris frequently. It was there that he met a distant cousin , Mom Rajawongse Sirikit Kitiyakara, daughter of the Thai ambassador to France and, thereafter, he regularly visited the amabssador’s family home. Whilst the relationship was developing Lek was seriously injured in a car accident. He lost an eye and needed to be hospitalized in Lausanne. Mom Rajawongse Sirikit (later known as Queen Sirikit) was a regular visitor and also met Sanguan, who suggested she continue her studies in Lausanne. She agreed and Lek chose Riante Rive, a boarding school in Lausanne for her. Their engagement came in Lausanne on July 19, 1949 and they were married the following year, on April 28, 1950. The couple went onto have four children: Princess Ubol Ratana, born on April 5, 1951; HRH Crown Prince Maha Vajiralongkorn, born July 28, 1952; HRH Crown Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn, born April 2, 1955 and HRH Princess Chulabhorn Walailak, born July 4, 1957. Lek’s coronation came a month after his marriage. It was an impressive event and gave him an indication of the latent influence the monarchy potentially had. News of the return of the king spread rapidly and, as he disembarked on Bangkok’s riverway, hundreds of thousands of cheering people greeted him. There were in fact two coronations – thee Spritiual Coronation of the late King Ananda (giving the deceased a fitting burial has great importance in Buddhism) and the new King’s. Both ceremonies were held within twelve days with a splendour that recalled the glories of the monarchical past. That the people still had a genuine veneration for the monarch Lek saw the evening after Nan’s cremation. Hundreds of thousands stayed with the late King’s ashes and Lek joined the crown anonymously. Dressed casually he was just another young Thai. The King had returned but it was a circumspect return reminsescent of King Ananda’s brief 1938 visit. With Marshall Pibul still in control of the country and the US prepared to support virtually any polity so long as it was not communist, Thailand was hostile territory politically, and to the people the King was more like a figure from a fairytale than a living, breathing monarch. Marshal Pibul’s jealousy had nonetheless been enrage and he was busy staging political provocations with the aim of having the King sign a new constitution that would, supposedly, restore Thai democracy, whilst in reality positioning himself for absolute power. Lek was better prepared for him now. He would later recall : “Political science textbooks in Lausanne were no use to me. I got more out of reading ‘Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Musashi’s Japanese ‘Book of Five Rings’ and Machiavelli’s ‘The Prince’. They were masters in the art of winning battles without waging open war.” So well did the King mask his true feelings his enemies were constantly surprised when he acted. The King’s return sparked an intricate game of political powerplays. Rather than appear in kingly regalia, Lek had stepped ashore in Bangkok wearing an ordinary suit so that the people would see the monarch was just like them. A deft populist touch to unbalance the politicians who saw him as little more than a spoilt brat who needed to be put in his place. Pibul’s game was to entrap the King in the capital and keep the countryfolk out with a military cordon whilst he was ‘convinced’ to sign the constitution. Instead Lek asked to see the great Buddhist temples and began an impromptu tour of the country; his instincts told him to show himself to the people. Politically it was also a tense time, with rumours of 200,000 Chinese troops preparing to invade Indochina. Thailand’s assigned role as a US ally in the cold war was as the South-East Asian nation that must, whatever the costs, not be allowed to fall to communism.  Despite this, Lek still refused to sign the constitution because it legitimised Pibul’s military rule under US patronage. Pibul and Lek were playing for high stakes and both trod carefully. The King’s way of delaying was to ask for more time to study the constitution. Lek in effect staged a royal filibuster. Corrupt and dissolute palace officials were worn down by long discussions after nights of debauchery, any royal drafts of the constitution were always carefully marked ‘provisional’ and Pibul’s offers of titular rewards if the King gave way were politely turned down. But Lek was isolated. The mystical aura that the moanrchy still had was no match for the might of the military and the pressure increased. The ruling clique now put out the rumour that the constitution had the royal signature and CIA operatives breathed a sigh of relief that this most vital cold war domino would not fall. They were fooled as Lek would not sign a document that removed his right to advise future governments; he had not returned to become a puppet of the military. The struggle over the constitution had been the military’s attempt to neuter the King. They failed but that did not lessen their dominance at the time and Lek’s early years were lonely, a subterranean existence lived behind ritual and symbolism, whilst he built up his prestige with the Thai people and cultivated his own spheres of influence as a counterweight to the military junta that ran the country. Marshall Pibul’s second period in power was facilitated by creating a façade of democracy rather than the overt militarism of the 1930s and 1940s. The reward was American aid in large quantities after Thailand’s entry into the Korean War as part of the United Nations’ multi-national force. However, under the surface the old tensions remained, militarism and tensions along the borders saw the creations of warlordism in the provinces and the anti-Chinese campaign was restarted. Thailand was at war, not all out war with its neighbours, but war nonetheless. The year of 1957, however, was an auspicious one for the King. Not only did his old foe fall from power, but his mother, Sanguan, returned to Thailand for the first time since the death of King Ananda. Deeply traumatised by her eldest son’s murder she had retreated into her studies and contemplated deeply about how to help her homeland. She was now ready to help Lek carry his burden and her work amongst Thailand’s poor agricultural people played a significant part in winning popular support for the monarchy. Lek and Sanguan’s shared philosophy was rooted in progressive European ideas of democracy and equality and Buddhism, which they felt were a natural combination. Lek described his political philosophy thus: “It’s not ‘socialism’ of a kind that frightens Americans. It’s like Jesus feeding thousands with a few loaves of fish. If we conserve our resources there’s enough to go around.” Sanguan had been shaken to her core by Nan’s death but her vitality now returned as she joined Lek’s quiet crusade and took upon herself the task of helping poor Thai families in the impoverished north of the country. Under her patronage medical facilities were built for the hill tribes and alternatives to the opium crop were found in an attempt to loosen the grip of the drug lords. Nonetheless, the strain of kingship took its toll on Lek and Sanguan worried about the effects on his health and on the family’s home life. Having been thrown into kingship just as he became a father for the first time, and having no real recollection of his own father who had died two years after he was born, Lek had to find his own way as a family man. He certainly lavished affection on Queen Sirikit and their four children but kept his inner turmoil to himself. His love for Sirikit was expressed in photographic portraits and striking portrait paintings, and he also had his beloved jazz music for consolation. It was, however, an incremental achievement under a dictatorship that lasted into the 1970s in a country still deeply traditional, religious and superstitious. The politics of the era were horrifying. South-East Asia was devastated by the Cold-War which raged very hot in Korea, Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. Thailand fared better but was hardly a sovereign state in the true sense; in reality a military base for American forces. It was Lek’s nature to search for opportunities rather than sink into despair and he felt there was a hopeful contemporary parallel in Marshall Tito’s Yugoslavia. The Balkan peninsula had some relevance to South-East Asia, long having been a region where great powers fought clandestinely and, in the late 1940s, Tito had stood up to the Soviet Union’s threats and gained worldwide admiration and, crucially, support from the West. What Tito gained was political support and money, which gave the country a chance for real progress. Lek, ever the diligent student, found out from French political channels about the true extent of Soviet-Chinese tensions and how Tito was using China as a counterbalance to Soviet influence. He wrote a textbook on Tito for Thai military cadets and had translated into Thai Phyllis Auty’s biography of the Yugoslav leader. What attracted Lek so much were Tito’s ideas of self-sufficient socialism, which aimed to free small nations from the clutches of great powers and create a stable and humane society. At the time Tito’s model seemed a striking success, particularly in a country containing several cultures which had fought each other bitterly for centuries. The crucial difference was, however, that the US and the Soviet Union had a detente in Europe. The NATO nations faced off against the Warsaw Pact and the Balkan nations were left more to their own devices as other regions – the Middle East, South-East Asia, Cuba – took on greater importance. It did not deflect Lek from his goals of a self-sufficient nation with a flourishing agricultural sector, but the reality was that the nation modernised and made progress, but it was under the pressure of militarism and with scant consideration of the long term socio-economic implications. Lek’s way – ‘The Poor Man’s Way’ – took a back seat to the immediate realities. The Cold War did not lead to nuclear confrontation and South-East Asia eventually emerged from its trauma, the pivotal moment coming with the US withdrawal from Vietnam in the 1970s. It was then that Thai democracy finally got a real chance. Field Marshal Thanom Kittikachorn was the last of Thailand’s military rulers. An era which had begun with the overthrow of the absolute monarchy by a small clique of politcians and generals in 1932, ended four decades later with a popular revolution that marked the beginning of the democratic age. Thanom was one of the “Three Tyrants”, along with his son Colonel Narong Kittikachorn, and Narong’s father-in-law, Field Marshal Praphas Charusathien, who ran the country during its last dictatorship. In October 1973 the capital saw enormous demonstrations calling for the end of military rule. The regime responded with force, and up to 70 demonstrators were killed in the streets. State brutality that Thailand had not seen for some years. This prompted the King to make his first direct intervention into politics by withdrawing his support for the military regime and, by October 14, 1973, Thanom had stepped down and left the country. A combination of the urban middle classes and students had overthrown the rule of the military. A new constitution was brought in and full democracy appeared to be on the way. External events, however, soon undermined the fledgling democracy. US withdrawal from Vietnam led to the victorious communists taking power in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia by 1975. Many who had supported the 1973 revolution began to have doubts. The communist regimes now on Thailand’s borders, the abolition of the 600-year-old Lao monarchy, along with an influx of refugees from Cambodia and Laos, drove public opinion in Thailand back to the Right-wing, and in the 1976 elections the conservatives gained ground. Rather than a new demorcratic consensus, the nation was becoming polarised. In October the hardliners made their move. Paramilitaries were sent in to crush the students, a feat achieved in particularly brutal fashion, after which thousands fled the country. The democratic revolution was swept away and the military resumed its role as the real government of the nation. It was a return to the bad old ways but by the early 1980s, with China ending its support for Thai Communists and the Khmer Rouge’s genocidal rule in Cambodia coming to an end, the chance to reinstate the democratic experiment re-emerged. Although the King’s sympathies were with the democrats there was ample evidence close to hand as to where revolutionary excesses could lead. He looked instead for a gradual democratisation and found an ally in General Prem Tinsulanonda, who saw that the King’s political experience was far greater than any contemporary politician. The events of 1981 gave them their chance. Military rule was not working and, in April 1981, a clique of army officers, known rather anachronistically as the “Young Turks,” staged the latest coup. They dissolved the National Assembly and promised sweeping change. Their authority evaporated when General Prem accompanied the royal family to Khorat in the north-east of the country. With the King’s support, Prem and loyalists units retook the capital without bloodshed. This episode raised the prestige of the monarchy still further and a compromise deal was reached. The insurrection against military rule was ended and most of the guerillas, who were formerly students, returned to Bangkok under an amnesty. The army returned to barracks, and a new constitution was promulgated, adding an appointed Senate to balance the popularly elected National Assembly. The elections of 1983 gave Prem a majority in the legislature. The shift back to democracy was also facilitated by the economic revolution which was sweeping across South-East Asia. After the recession of the mid 1970s, economic growth surged. For the first time in its history Thailand became a significant industrial power, and a centre of manufacture. With the end of the Indochina wars and the domestic insurgency, tourism also developed rapidly and became a major boon. The urban population continued to grow rapidly, but the overall population began to decline, which fortuituously led to a rise in living standards even amongst the poor rural areas. Thailand’s economic boom did not match that of the “Asian tigers” such as Taiwan and South Korea, but a period of sustained growth ensued. Prem thereby stayed in office for eight years through two more general elections in 1983 and 1986. His personal popularity remained high but growing urban confidence saw a revival of democratic politics and the demand for a more adventurous leader. The 1988 elections brought another former General Chatichai Choonhavan to power. However, Chatichai’s government was incompetent and corrupt. What it showed was that the shadow of military rule was still a long one. By allowing one faction of the military to get rich on government contracts, he antagonised a rival faction, led by Generals Sunthorn Kongsompong and Suchinda Kraprayoon, who staged a coup in February 1991. This faction brought in a civilian prime minister, Anand Panyarachun, who was still responsible to the military in the form of the National Peacekeeping Council with General Sunthorn as chairman. It was some improvement as Anand’s anti-corruption drive proved popular. Another general election was held in 1992, as has become the custom following a coup in Thailand. In March 1992, the military strongman General Suchinda accepted the invitation from a coalition of parties to become prime minister, reneging on a promise he had made earlier to the King and confirming the fear that the new government was a military regime thinly veiled. However, the Thailand of 1992 was hardly the nation of 1932 and Suchinda’s arrogance brought hundreds of thousands of people out in the largest demonstrations ever seen in Bangkok, led by the former governor of Bangkok, Major-General Chamlong Srimuang. Suchinda brought in military units personally loyal to him and tried to deal with the demonstrators by force. The result was a massacre in the heart of the city in which hundreds died. The Navy mutinied in protest, and the country seemed on the brink of a civil war. In May the King intervened: he summoned Suchinda and Chamlong to a televised audience. It brought Suchinda’s resignation. The King re-appointed Anand Panyarachun as prime minister until elections could be held in September 1992. They brought the Democrat Party into office under Chuan Leekpai, the first Thai premier to gain power without the backing of the military. He represented the liberal voters of Bangkok and the south. A competent administrator, Chuan stayed in power until 1995, when he was defeated at elections by a coalition of conservative and provincial parties. The new administration was mired in corruption allegations from the very beginning and was forced to call early elections in 1996, in which General Chavalit Yongchaiyudh’s New Aspiration Party managed to gain a narrow victory. The crucial point in this period was the financial crisis that hit Asia in 1997. The crisis began in July in Thailand and quickly affected currencies and stock markets, in several Asian countries. Apart from Thailand, Indonesia, South Korea, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Laos and the Phillipines were all significantly affected. It led to the fall of the government and the return of Chuan Leekpai who made an arrangement with the IMF that helped stabilise the country, which was followed by the populist aappeal of Thaksin Shinawatra The first part of the twenty-first century bears the stamp of Thaksin Shinawatra. His is not the worst government that Thailand has experienced, but it is a long way from the self-sufficiency and social justice that King Bhumibol has so patiently striven for. But to judge the King’s role in purely material terms is to miss the point. If Lek remains an idealist at heart, he is a political realist and his Buddhist faith tells him that before society can change the heart must change. Lek has never fallen into the error of thinking that society can be forced to become more harmonious and more tolerant. A great deal has been achieved and a great deal more needs to be done, but the true strength and, indeed, revolutionary aspect of King Bhumibol’s reign is his constancy and the respect he enjoys, both as a man and monarch, have been well earned. (Royalty Magazine Vol. 20/02)

Despite this, Lek still refused to sign the constitution because it legitimised Pibul’s military rule under US patronage. Pibul and Lek were playing for high stakes and both trod carefully. The King’s way of delaying was to ask for more time to study the constitution. Lek in effect staged a royal filibuster. Corrupt and dissolute palace officials were worn down by long discussions after nights of debauchery, any royal drafts of the constitution were always carefully marked ‘provisional’ and Pibul’s offers of titular rewards if the King gave way were politely turned down. But Lek was isolated. The mystical aura that the moanrchy still had was no match for the might of the military and the pressure increased. The ruling clique now put out the rumour that the constitution had the royal signature and CIA operatives breathed a sigh of relief that this most vital cold war domino would not fall. They were fooled as Lek would not sign a document that removed his right to advise future governments; he had not returned to become a puppet of the military. The struggle over the constitution had been the military’s attempt to neuter the King. They failed but that did not lessen their dominance at the time and Lek’s early years were lonely, a subterranean existence lived behind ritual and symbolism, whilst he built up his prestige with the Thai people and cultivated his own spheres of influence as a counterweight to the military junta that ran the country. Marshall Pibul’s second period in power was facilitated by creating a façade of democracy rather than the overt militarism of the 1930s and 1940s. The reward was American aid in large quantities after Thailand’s entry into the Korean War as part of the United Nations’ multi-national force. However, under the surface the old tensions remained, militarism and tensions along the borders saw the creations of warlordism in the provinces and the anti-Chinese campaign was restarted. Thailand was at war, not all out war with its neighbours, but war nonetheless. The year of 1957, however, was an auspicious one for the King. Not only did his old foe fall from power, but his mother, Sanguan, returned to Thailand for the first time since the death of King Ananda. Deeply traumatised by her eldest son’s murder she had retreated into her studies and contemplated deeply about how to help her homeland. She was now ready to help Lek carry his burden and her work amongst Thailand’s poor agricultural people played a significant part in winning popular support for the monarchy. Lek and Sanguan’s shared philosophy was rooted in progressive European ideas of democracy and equality and Buddhism, which they felt were a natural combination. Lek described his political philosophy thus: “It’s not ‘socialism’ of a kind that frightens Americans. It’s like Jesus feeding thousands with a few loaves of fish. If we conserve our resources there’s enough to go around.” Sanguan had been shaken to her core by Nan’s death but her vitality now returned as she joined Lek’s quiet crusade and took upon herself the task of helping poor Thai families in the impoverished north of the country. Under her patronage medical facilities were built for the hill tribes and alternatives to the opium crop were found in an attempt to loosen the grip of the drug lords. Nonetheless, the strain of kingship took its toll on Lek and Sanguan worried about the effects on his health and on the family’s home life. Having been thrown into kingship just as he became a father for the first time, and having no real recollection of his own father who had died two years after he was born, Lek had to find his own way as a family man. He certainly lavished affection on Queen Sirikit and their four children but kept his inner turmoil to himself. His love for Sirikit was expressed in photographic portraits and striking portrait paintings, and he also had his beloved jazz music for consolation. It was, however, an incremental achievement under a dictatorship that lasted into the 1970s in a country still deeply traditional, religious and superstitious. The politics of the era were horrifying. South-East Asia was devastated by the Cold-War which raged very hot in Korea, Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. Thailand fared better but was hardly a sovereign state in the true sense; in reality a military base for American forces. It was Lek’s nature to search for opportunities rather than sink into despair and he felt there was a hopeful contemporary parallel in Marshall Tito’s Yugoslavia. The Balkan peninsula had some relevance to South-East Asia, long having been a region where great powers fought clandestinely and, in the late 1940s, Tito had stood up to the Soviet Union’s threats and gained worldwide admiration and, crucially, support from the West. What Tito gained was political support and money, which gave the country a chance for real progress. Lek, ever the diligent student, found out from French political channels about the true extent of Soviet-Chinese tensions and how Tito was using China as a counterbalance to Soviet influence. He wrote a textbook on Tito for Thai military cadets and had translated into Thai Phyllis Auty’s biography of the Yugoslav leader. What attracted Lek so much were Tito’s ideas of self-sufficient socialism, which aimed to free small nations from the clutches of great powers and create a stable and humane society. At the time Tito’s model seemed a striking success, particularly in a country containing several cultures which had fought each other bitterly for centuries. The crucial difference was, however, that the US and the Soviet Union had a detente in Europe. The NATO nations faced off against the Warsaw Pact and the Balkan nations were left more to their own devices as other regions – the Middle East, South-East Asia, Cuba – took on greater importance. It did not deflect Lek from his goals of a self-sufficient nation with a flourishing agricultural sector, but the reality was that the nation modernised and made progress, but it was under the pressure of militarism and with scant consideration of the long term socio-economic implications. Lek’s way – ‘The Poor Man’s Way’ – took a back seat to the immediate realities. The Cold War did not lead to nuclear confrontation and South-East Asia eventually emerged from its trauma, the pivotal moment coming with the US withdrawal from Vietnam in the 1970s. It was then that Thai democracy finally got a real chance. Field Marshal Thanom Kittikachorn was the last of Thailand’s military rulers. An era which had begun with the overthrow of the absolute monarchy by a small clique of politcians and generals in 1932, ended four decades later with a popular revolution that marked the beginning of the democratic age. Thanom was one of the “Three Tyrants”, along with his son Colonel Narong Kittikachorn, and Narong’s father-in-law, Field Marshal Praphas Charusathien, who ran the country during its last dictatorship. In October 1973 the capital saw enormous demonstrations calling for the end of military rule. The regime responded with force, and up to 70 demonstrators were killed in the streets. State brutality that Thailand had not seen for some years. This prompted the King to make his first direct intervention into politics by withdrawing his support for the military regime and, by October 14, 1973, Thanom had stepped down and left the country. A combination of the urban middle classes and students had overthrown the rule of the military. A new constitution was brought in and full democracy appeared to be on the way. External events, however, soon undermined the fledgling democracy. US withdrawal from Vietnam led to the victorious communists taking power in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia by 1975. Many who had supported the 1973 revolution began to have doubts. The communist regimes now on Thailand’s borders, the abolition of the 600-year-old Lao monarchy, along with an influx of refugees from Cambodia and Laos, drove public opinion in Thailand back to the Right-wing, and in the 1976 elections the conservatives gained ground. Rather than a new demorcratic consensus, the nation was becoming polarised. In October the hardliners made their move. Paramilitaries were sent in to crush the students, a feat achieved in particularly brutal fashion, after which thousands fled the country. The democratic revolution was swept away and the military resumed its role as the real government of the nation. It was a return to the bad old ways but by the early 1980s, with China ending its support for Thai Communists and the Khmer Rouge’s genocidal rule in Cambodia coming to an end, the chance to reinstate the democratic experiment re-emerged. Although the King’s sympathies were with the democrats there was ample evidence close to hand as to where revolutionary excesses could lead. He looked instead for a gradual democratisation and found an ally in General Prem Tinsulanonda, who saw that the King’s political experience was far greater than any contemporary politician. The events of 1981 gave them their chance. Military rule was not working and, in April 1981, a clique of army officers, known rather anachronistically as the “Young Turks,” staged the latest coup. They dissolved the National Assembly and promised sweeping change. Their authority evaporated when General Prem accompanied the royal family to Khorat in the north-east of the country. With the King’s support, Prem and loyalists units retook the capital without bloodshed. This episode raised the prestige of the monarchy still further and a compromise deal was reached. The insurrection against military rule was ended and most of the guerillas, who were formerly students, returned to Bangkok under an amnesty. The army returned to barracks, and a new constitution was promulgated, adding an appointed Senate to balance the popularly elected National Assembly. The elections of 1983 gave Prem a majority in the legislature. The shift back to democracy was also facilitated by the economic revolution which was sweeping across South-East Asia. After the recession of the mid 1970s, economic growth surged. For the first time in its history Thailand became a significant industrial power, and a centre of manufacture. With the end of the Indochina wars and the domestic insurgency, tourism also developed rapidly and became a major boon. The urban population continued to grow rapidly, but the overall population began to decline, which fortuituously led to a rise in living standards even amongst the poor rural areas. Thailand’s economic boom did not match that of the “Asian tigers” such as Taiwan and South Korea, but a period of sustained growth ensued. Prem thereby stayed in office for eight years through two more general elections in 1983 and 1986. His personal popularity remained high but growing urban confidence saw a revival of democratic politics and the demand for a more adventurous leader. The 1988 elections brought another former General Chatichai Choonhavan to power. However, Chatichai’s government was incompetent and corrupt. What it showed was that the shadow of military rule was still a long one. By allowing one faction of the military to get rich on government contracts, he antagonised a rival faction, led by Generals Sunthorn Kongsompong and Suchinda Kraprayoon, who staged a coup in February 1991. This faction brought in a civilian prime minister, Anand Panyarachun, who was still responsible to the military in the form of the National Peacekeeping Council with General Sunthorn as chairman. It was some improvement as Anand’s anti-corruption drive proved popular. Another general election was held in 1992, as has become the custom following a coup in Thailand. In March 1992, the military strongman General Suchinda accepted the invitation from a coalition of parties to become prime minister, reneging on a promise he had made earlier to the King and confirming the fear that the new government was a military regime thinly veiled. However, the Thailand of 1992 was hardly the nation of 1932 and Suchinda’s arrogance brought hundreds of thousands of people out in the largest demonstrations ever seen in Bangkok, led by the former governor of Bangkok, Major-General Chamlong Srimuang. Suchinda brought in military units personally loyal to him and tried to deal with the demonstrators by force. The result was a massacre in the heart of the city in which hundreds died. The Navy mutinied in protest, and the country seemed on the brink of a civil war. In May the King intervened: he summoned Suchinda and Chamlong to a televised audience. It brought Suchinda’s resignation. The King re-appointed Anand Panyarachun as prime minister until elections could be held in September 1992. They brought the Democrat Party into office under Chuan Leekpai, the first Thai premier to gain power without the backing of the military. He represented the liberal voters of Bangkok and the south. A competent administrator, Chuan stayed in power until 1995, when he was defeated at elections by a coalition of conservative and provincial parties. The new administration was mired in corruption allegations from the very beginning and was forced to call early elections in 1996, in which General Chavalit Yongchaiyudh’s New Aspiration Party managed to gain a narrow victory. The crucial point in this period was the financial crisis that hit Asia in 1997. The crisis began in July in Thailand and quickly affected currencies and stock markets, in several Asian countries. Apart from Thailand, Indonesia, South Korea, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Laos and the Phillipines were all significantly affected. It led to the fall of the government and the return of Chuan Leekpai who made an arrangement with the IMF that helped stabilise the country, which was followed by the populist aappeal of Thaksin Shinawatra The first part of the twenty-first century bears the stamp of Thaksin Shinawatra. His is not the worst government that Thailand has experienced, but it is a long way from the self-sufficiency and social justice that King Bhumibol has so patiently striven for. But to judge the King’s role in purely material terms is to miss the point. If Lek remains an idealist at heart, he is a political realist and his Buddhist faith tells him that before society can change the heart must change. Lek has never fallen into the error of thinking that society can be forced to become more harmonious and more tolerant. A great deal has been achieved and a great deal more needs to be done, but the true strength and, indeed, revolutionary aspect of King Bhumibol’s reign is his constancy and the respect he enjoys, both as a man and monarch, have been well earned. (Royalty Magazine Vol. 20/02)